Preface

Readers of my blog will know that I typically maintain a pretty casual tone. This post was originally written for an academic setting, so hang with me if you find yourself slogging through a bit denser material this time.

Abstract

The MOVEit transfer campaign, orchestrated by the CL0P ransomware gang, targeted a wide range of victims, employing a zero-day attack that exploited a common SQL injection technique. Ongoing identification of victims is facilitated through various sources, including news headlines, official reports, and leaks from the CL0P^_-LEAKS onion site. In light of this incident, this study advocates for enhanced security measures through increased transparency in code repositories, leveraging open-source methodologies.

1 INTRODUCTION

The MOVEit data breaches emerged as the largest to date this year. Whenever a major event such as this one occurs, cybersecurity analysts and policy makers must take a moment to pause and reflect on the critical industry failures which lead to the event and to ask difficult questions with the hopes of preventing future recurrences. This report breaks down the incident in detail and proposes possible mitigation efforts at the organizational policy level.

2 INCIDENT DESCRIPTION

2.1 Background

The uniqueness of the MOVEit data breaches stem from the size and scope of these incidents. The perpetrators utilized a SQL injection attack to deliver their ransomware which consists of entering unexpected input into a vulnerable web application with improper validation or sanitization. Every year Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP) publishes the top ten web application vulnerabilities and SQL injection routinely makes the list. As host of the Security Now podcast, Steve Gibson, laments, SQL injection has been around for a long time and was first documented in 1998 by cybersecurity researcher and hacker Jeff Forristal (Gibson, 2023). Despite this common tactic, news of the breach dominated headlines for much of June 2023 due to the magnitude of data and victims impacted.

2.2 Sequence of Events

While some events may be apparent, others have only come to light as researchers delve into forensic data with fresh insights.

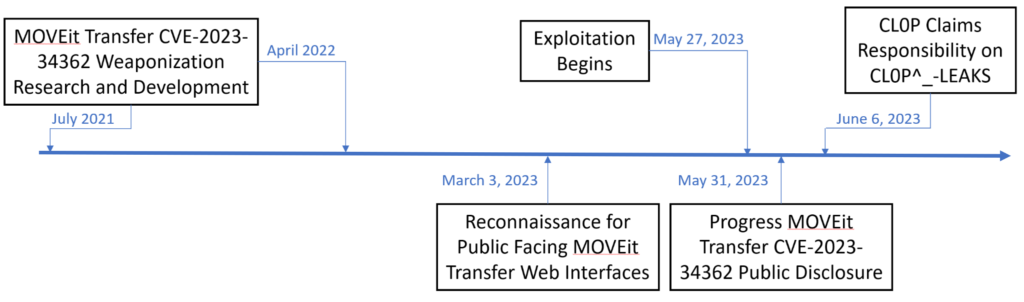

* Kroll’s investigations suggest that the MOVEit Transfer vulnerability exploit was possibly tested or used in July 2021 and April 2022 (Downie et al., 2023).

* Greynoise has detected unidentified threat actors scanning publicly accessible MOVEit Transfer login pages as early as March 3, 2023 (Remacle, 2023).

* The earliest evidence of exploitation can be traced back to Labor Day weekend, specifically May 27th (Zaveri et al., 2023).

* On May 31st, Progress Software Corporation publicly disclosed the MOVEit Transfer vulnerability (CVE-2023-34362) on their website.

* Subsequently, on June 6th, CL0P claimed responsibility for the attacks in a post on their data leak site, CL0P^_-LEAKS (Zaveri et al., 2023).

Figure 1— Timeline of Events

2.3 Fallout

Given the recent occurrence of the MOVEit Transfer breaches, the full extent of the incident is still unfolding. As of June 29th, the sensitive information of over 16 million people and at least 158 organizations have been compromised (Greig, 2023a). Notably, this breach has taken a slightly different approach compared to the conventional ransomware extortion tactics. Instead of directly contacting the victims for ransom negotiations, CL0P chose to list their victims on a leak site and demanded that the affected parties initiate contact to discuss payment for not publicizing their data.

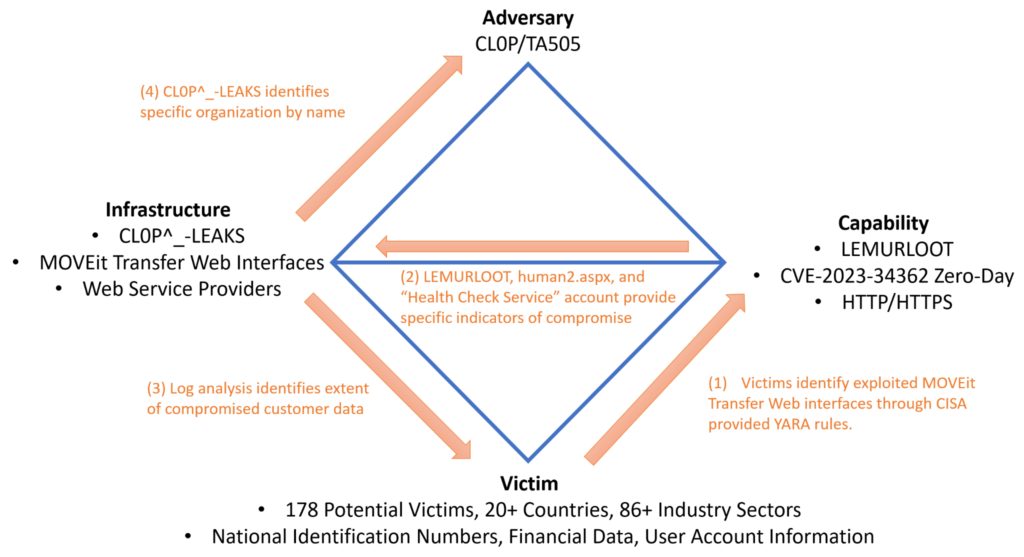

3 DIAMOND MODEL ANALYSIS

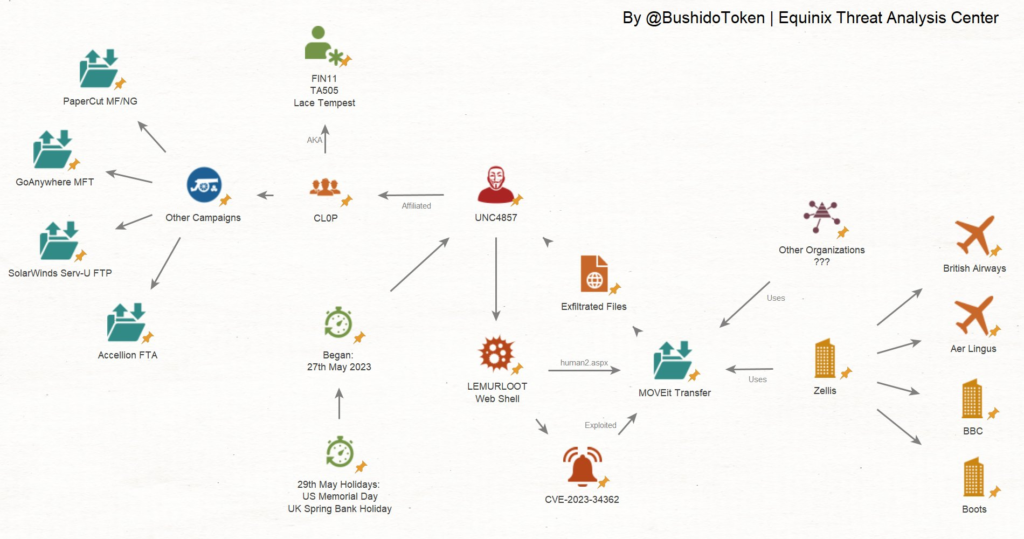

Although not strictly aligned with Georgia Tech’s standards for diamond model analysis, Curated Intel has created a GitHub page for tracking the MOVEit transfer hacking campaign (Token et al., 2023).

Figure 2— Maltego Example Summary from Curated Intel’s GitHub Repository

3.1 Adversary

Based on the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), MOVEit Transfer exploitation has been attributed by multiple sources with high confidence to TA505; affiliated with CL0P, UNC4857, and FIN11. CL0P first emerged in the Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) business in large spear-phishing campaigns back in February of 2019 and is known for ‘double extortion’ tactics of stealing encrypted data and threatening to publish sensitive information online. TA505 has compromised over 11,000 organizations and offers initial access broker (IAB) services, purchases IAB services, and runs large botnets in addition to RaaS (#StopRansomware: CL0P Ransomware, 2023). Primarily motivated by financial gains, TA505 is believed to be based in eastern Europe and appears to be both adversarial operator and customer in this campaign as no evidence has emerged to suggest otherwise.

3.2 Victims

CL0P’s ransomware campaign displays a broad-reaching impact that transcends national borders and targets organizations across diverse industry sectors, irrespective of their size or specific victim persona. As reported by Kon Briefing, there are 178 named potential victims spanning at least 20 countries and more than 86 industries, encompassing private, public, and government sectors (Kondruss, 2023). Victims’ assets range from financial to personal identity information based on the specific organization. Sources for identifying victims include the CL0P^_-LEAKS onion site, news headlines, and official government reporting channels. The commonality amongst all the victims is their susceptibility to reliance on insecure software design practices.

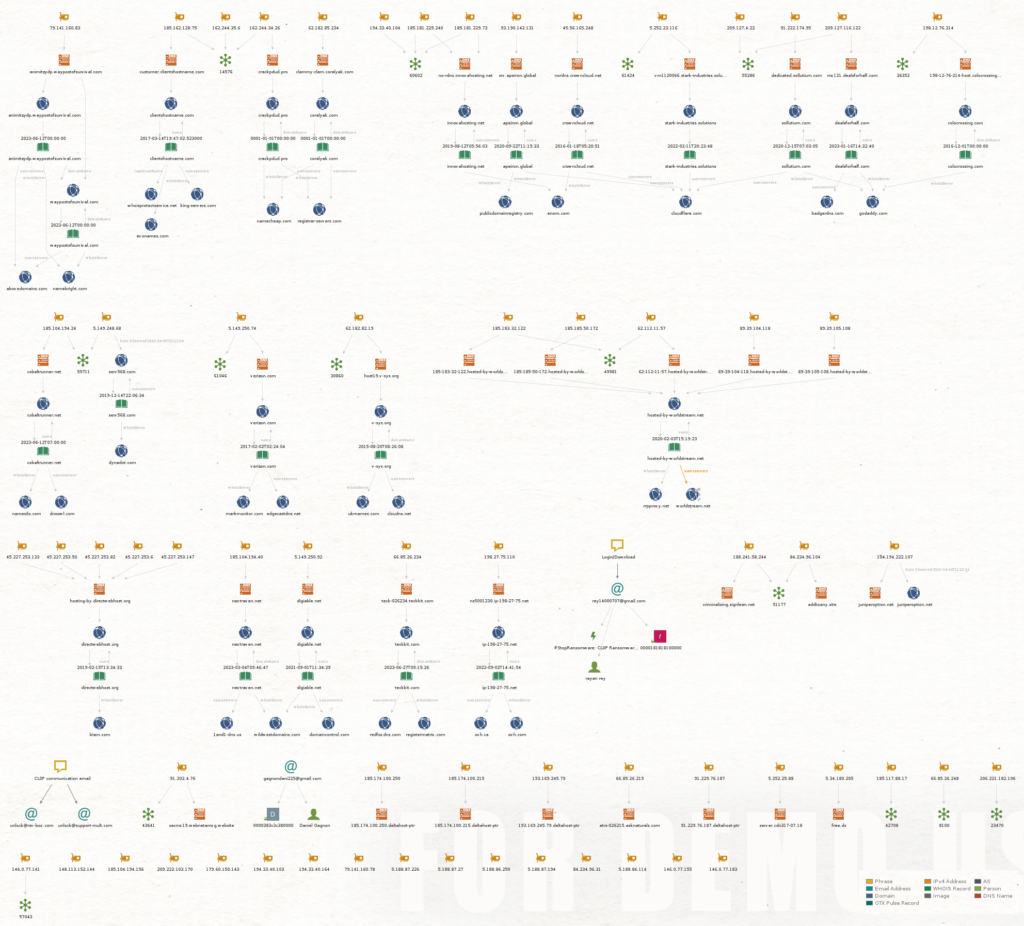

3.3 Infrastructure

CL0P predominantly relied on service providers to host their type 1 infrastructure. While CISA does not elaborate on the specific purpose of each instance, their report offers comprehensive details about TA505’s infrastructure used in both the MOVEit campaign and the previous Fortra GoAnywhere incident. The provided information includes domain names, IP addresses, emails, and certificates associated with TA505 (#StopRansomware: CL0P Ransomware, 2023). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the various types of infrastructure utilized during the MOVEit campaign. Additionally, it is worth mentioning the existence of the onion site where CL0P claimed responsibility for the attacks and directed victims to obtain further information regarding ransom payment negotiations. This site serves as a communication channel for the threat actor.

Figure 3— Maltego Graph of MOVEit Campaign Infrastructure

3.4 Capability

The MOVEit transfer campaign represents only a smaller subset of the capacity of TA505’s full arsenal. Indeed, TA505 is known for frequently changing malware and was as recently as January involved in another campaign targeting the GoAnywhere MFT platform (#StopRansomware: CL0P Ransomware, 2023). The CISA security alert goes on to elaborate on some of their other common exploits include FlawedAmmyy/FlawedGrace, SDBot, Truebot, Cobalt Strike, DEWMODE, and LEMURLOOT – the latter being utilized in the MOVEit transfer campaign. Exploitation involved the installation of LEMURLOOT utilizing a SQL injection vulnerability to install a web shell for command and control (C2). The web shell, disguised as the legitimate file human.aspx, is named human2.aspx and allows for additional access through more SQL queries for database enumeration, file storage and retrieval, and the creation/deletion of additional accounts such as ‘Health Check Service.’

3.5 Meta-Features Analysis

The social-political meta feature of the adversary-to-victim relationship strongly indicates financially driven motivations with ties to eastern Europe. Although the targeted countries span a wide range, the United States suffered the majority of the attacks, notably coinciding with an American holiday. CL0P identified a common software vulnerability and demonstrated persistent adversarial tendencies in developing, testing, and identifying victims of opportunity. While government organizations have reported being victimized, CL0P has explicitly stated a lack of interest in extorting government, city, or police services, suggesting an absence of political motivations. Perhaps CL0P may have learned something about self-preservation from DarkSide’s past mistakes (Abrams, 2021). Traditional ransomware exploitation attacks the availability of the data by encrypting it and demanding payment for the decryption keys; however, the CL0P MOVEit transfer campaign jumps straight to attacking the confidentiality of the data through threats of public disclosure.

The technology meta-feature of the MOVEit breach primarily stemmed from insecure software development practices. In terms of the Cyber Kill Chain® framework by Lockheed Martin, CL0P took their time in the weaponization phase beginning in July of 2021 (Downie et al., 2023). The reconnaissance phase began in March when CL0P started its search for public facing MOVEit interfaces, approximately three months prior to the delivery and exploitation of the SQL vulnerability (Remacle, 2023). The LEMURLOOT kit provided the C2 platform for additional installation of malware in order to take the final actions on exfiltration of data. The MOVEit transfer service operates on HTTP, HTTPS, SFTP, and FTP; however, the vulnerability assessment identified only the HTTP and HTTPS services as vulnerable, emphasizing the recommendation to disable these services until appropriate patches have been applied (MOVEit Transfer Critical Vulnerability, 2023).

Figure 4— Diamond Model Summary Graph

4 POLICY ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

4.1 Policy Assessment

Before proceeding with recommendations, we pause to consider the limitations of relying solely on a compliance-based approach. Progress advertises in its opening introduction to the MOVEit software that it is PCI, HIPAA, and GDPR compliant. Of course, the Progress MOVEit breach is not an anomaly among compliant software vendors. Several factors contribute to the failure of security management through compliance, including misalignment of business and security incentives, lack of technical proficiency among auditors, limited transparency of audited organizations, inadequate penalties, and the inability of compliance standards to keep pace with rapidly evolving innovations.

4.1 Recommendations

Change must come at the organizational level through prioritization of open-source solutions, shifting the burden of cybersecurity from private entities to the public domain. As early as 2005, Clarke, Dorwin, and Nash highlighted the flaws of the “security through obscurity” approach in proprietary solutions and extolled the benefits of open-source software (Clarke et al., 2005). In recent years, the zero trust network approach has gained significant popularity. However, proprietary services inherently contradict this approach as they necessitate a high level of trust in a product’s integrity as guaranteed by the vendor. Attackers utilize this trust to their advantage in a growing trend towards software supply chain compromise.

Bug bounty programs already align with the open-source methodology by fostering collaboration with external researchers, facilitating communication with software vendors, and promoting transparency through clear rules of engagement. Nevertheless, closed-source solutions often hinder these benefits unless researchers have reasonable expectations of returns for their investment in reverse-engineering the product. In the case of Progress MOVEit software, both an internally hired cybersecurity firm, Huntress, and an external researcher named MCKSys Argentina identified critical vulnerabilities within a month of the original zero-day vulnerability (Greig, 2023b). Considering that the vulnerability extends to versions as far back as June of 2021, a more collaborative environment might have detected these flaws much sooner. Incidents like this reinforce the notion that fear of competition, rather than security, drives proprietary software vendors.

The burden of transitioning to open-source technologies lies primarily with the demand side of the market’s supply and demand dynamics. It is unrealistic to expect suppliers to freely disclose their proprietary technologies due to significant financial incentives. However, if organizations were to favor open-source products over their proprietary competitors, the market could eventually experience a course correction. Furthermore, compliance auditors could then shift from reviewing generic standards applied to closed systems to specific open-source implementations. The resulting socio-economic impact would be the transformation of security from a private to a public good.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In summary, securing an organization’s software supply chain proves to be one of the most challenging tasks. In the MOVEit transfer campaign, CL0P found the mistake and spent years preparing for its exploitation. Sadly, their slowness to act upon the vulnerability could also be seen as an indication of confidence that Progress would not find and remediate the vulnerability in the meantime. Software developers must continually balance product delivery with secure design and get it right every time. On the other hand, attackers only need to exploit a single mistake to gain an entry point. Given the unequal playing field, open-source software presents one method of making the odds more favorable through crowdsourcing of services. To think that open-source software presents some sort of silver bullet would be naive; however, it is the author’s opinion that it would certainly be a step in the right direction for the overall security landscape.

6 REFERENCES

1. #StopRansomware: CL0P Ransomware Gang Exploits CVE-2023-34362 MOVEit Vulnerability. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. (2023, June 7). https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-158a

2. Abrams, L. (2021, May 14). DarkSide ransomware servers reportedly seized, operation shuts down. BleepingComputer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/darkside-ransomware-servers-reportedly-seized-operation-shuts-down/

3. Caltagirone, S., Pendergast, A., & Betz, C. (2013, July). The Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis. https://www.activeresponse.org/. https://www.activeresponse.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/diamond.pdf

4. Clarke, R., Dorwin, D., & Nash, R. (2005). (rep.). Is Open Source Software More Secure? Retrieved July 5, 2023, from https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/csep590/05au/whitepaper_turnin/oss(10).pdf.

5. Downie, S., Ackerman, D., Iacono, L., & Cox, D. (2023, June 8). Clop Ransomware Likely Sitting on MOVEit Transfer Vulnerability (CVE-2023-34362) Since 2021 . Kroll. https://www.kroll.com/en/insights/publications/cyber/clop-ransomware-moveit-transfer-vulnerability-cve-2023-34362

6. Gibson, S. (2023, June 20). The Massive MOVEit Maelstrom (No. 928) [Audio podcast episode]. In Security Now. https://podcasts.apple.com/my/podcast/the-massive-moveit-maelstrom-patch-tuesday-spinrite-7/id79016499?i=1000617785970

7. Greig, J. (2023a, June 29). More than 16 million people and counting have had data exposed in MOVEit breaches. The Record from Recorded Future News. https://therecord.media/data-of-sixteen-million-exposed-moveit

8. Greig, J. (2023b, June 16). Third MOVEIT vulnerability raises alarms as US agriculture department says it may be impacted. The Record from Recorded Future News. https://therecord.media/third-moveit-vulnerability-raises-alarms

9. Kondruss, B. (2023, May 31). Moveit Hack Victim list. KonBriefing.com. https://konbriefing.com/en-topics/cyber-attacks-moveit-victim-list.html

10. MOVEit Transfer Critical Vulnerability (May 2023) (CVE-2023-34362). Progress Community. (2023, May 31). https://community.progress.com/s/article/MOVEit-Transfer-Critical-Vulnerability-31May2023

11. Remacle, M. (2023, June 1). Progress’ MOVEit Transfer Critical Vulnerability: CVE-2023-34362. Greynoise. https://www.greynoise.io/blog/progress-moveit-transfer-critical-vulnerability

12. Token, B., Marchive, V., Davis, C., & Orchilles, J. (2023, June 16). MOVEit Transfer Hacking Campaign Tracking. GitHub. https://github.com/curated-intel/MOVEit-Transfer/

13. Zaveri, N., Kennelly, J., Stark, G., Mcwhirt, M., Nutting, D., Goody, K., Moore, J., Pisano, J., Work, Z., Ukhanov, P., Sucik, J., Silverstone, W., Schramm, Z., Blaum, G., Styles, O., Bennett, N., & Murchie, J. (2023, June 2). Zero-Day Vulnerability in MOVEit Transfer Exploited for Data Theft. Mandiant: Now Part of Google Cloud. https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/zero-day-moveit-data-theft